‘Buy Canadian,’ eh? It’s Complicated

Canadian grocery store

I am not affiliated with any brands and products that I share in this post. I am an independent researcher sharing my knowledge to help consumers shop their values. Where stated have I personally tried and recommend brands or products. I’m always hopeful to receive feedback from the community about your experiences.

3 Questions to Ask Before Sailing into the Buy Canadian Wave

The first question to ask yourself before buying into the ‘Buy Canadian’ movement is, what are you hoping to achieve? If your goal is to support Canadian producers and companies, the Canadian economy, and Canadian people, your act of buying Canadian may in fact be at odds with your values and goals. This caution is particularly valuable when it comes to groceries and especially if you’re not informed on how food goods get to the shelf.

Buying ‘Canadian’ food is really complicated! Many mainstream products come from long, integrated, and turbid supply chains. The act of buying Canadian means understanding supply chains and origin claims. It means increasing your knowledge and demanding transparency about where your food comes from. Unfortunately, buying Canadian is not as simple as following a maple leaf, a claim like ‘Made in Canada,’ or a patriotic narrative. I know, I know… logistics and legalities, not sexy stuffy. The truth rarely is. Lucky for you, Ruby Rooster is here to make it easier.

If, like Ahab, you are determined to navigate this ocean of patriotic sentiment, I commend you for doing what you believe in, BUT BUYER BEWARE. I’m here to help you shop your values and not get dragged out to sea.

In this post I’ll provide useful resources and critical considerations about buying Canadian, including:

What is a Canadian product anyway?

‘Local’

‘Product of Canada’

‘Made in Canada’

Complications with claims

Who is benefitting from your dollars and where? Canadian companies, Canadian retailers and Canadian producers.

What ‘Buy Canadian’ could be if we’re smart about it

What is a Canadian Product?

What is a Canadian product anyway? It is critical to know that there is a difference between labels (e.g. nutrition facts) and claims, and that most claims in Canada are voluntary and used for marketing. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), the enforcement arm of Health Canada, has a pretty good resource for evaluating origin and other claims, here. A summary of the basics for buying Canadian follows.

‘Local’ is kind of the gold standard if you want to buy Canadian. According to CFIA policy, local means produced within the province or territory sold, or sold across provincial borders within 50 km of the originating province or territory. The term ‘Local’ then, implies that something is produced in Canada. That’s pretty much as good as you’re going to get.

‘Product of Canada’ is also a fairly solid claim for the buy Canadian movement. It means that nearly all ingredients, processing and labour are Canadian and that 98% of the direct cost of production was Canadian.[i] Similarly, the CFIA considers claims like ‘Canadian,’ or ‘100% Canadian,’ similar to ‘Product of Canada.’

‘Made in Canada,’ is probably the most prolific claim out there right now and it is the least ‘Canadian’ claim to be made. According to the CFIA, ‘Made in Canada’ means that the last substantial transformation or process occurred in Canada. A substantial transformation is a change in form, appearance or nature that essentially makes it a new product. For example, fresh fish to canned fish. It means that businesses and people located in Canada were involved in the final stages of production and that 51% of the direct cost of production was in Canada. The CFIA considers similar claims like ‘Produced in Canada, or ‘Manufactured in Canada,’ similar to ‘Made in Canada.’ A qualifying statement like ‘Made in Canada from imported ingredients’ or ‘Made in Canada from domestic and imported ingredients’ accompanies the ‘Made in Canada’ claim.[ii]

There are some complications with claims that sink any purist version of buy Canadian sentiment, no matter what claim is made. To start, inputs like seeds, fertilizers, feed, medications, and packaging materials are not considered part of the cost of production.[iii] Neither are indirect costs, like transportation and overhead, or machinery, for example. It is also not clear if the businesses located in Canada need to be Canadian owned or can be a foreign subsidiary. It’s not clear whether workers need to be Canadian citizens or permanent residents, they could simply hold work permits too. So aside from some business taxes, property taxes, and personal income taxes, some potential contributions to GDP though business investment or exports, there is little guarantee of a benefit to Canada, or Canadians from buying a product with a ‘Made in Canada’ claim.

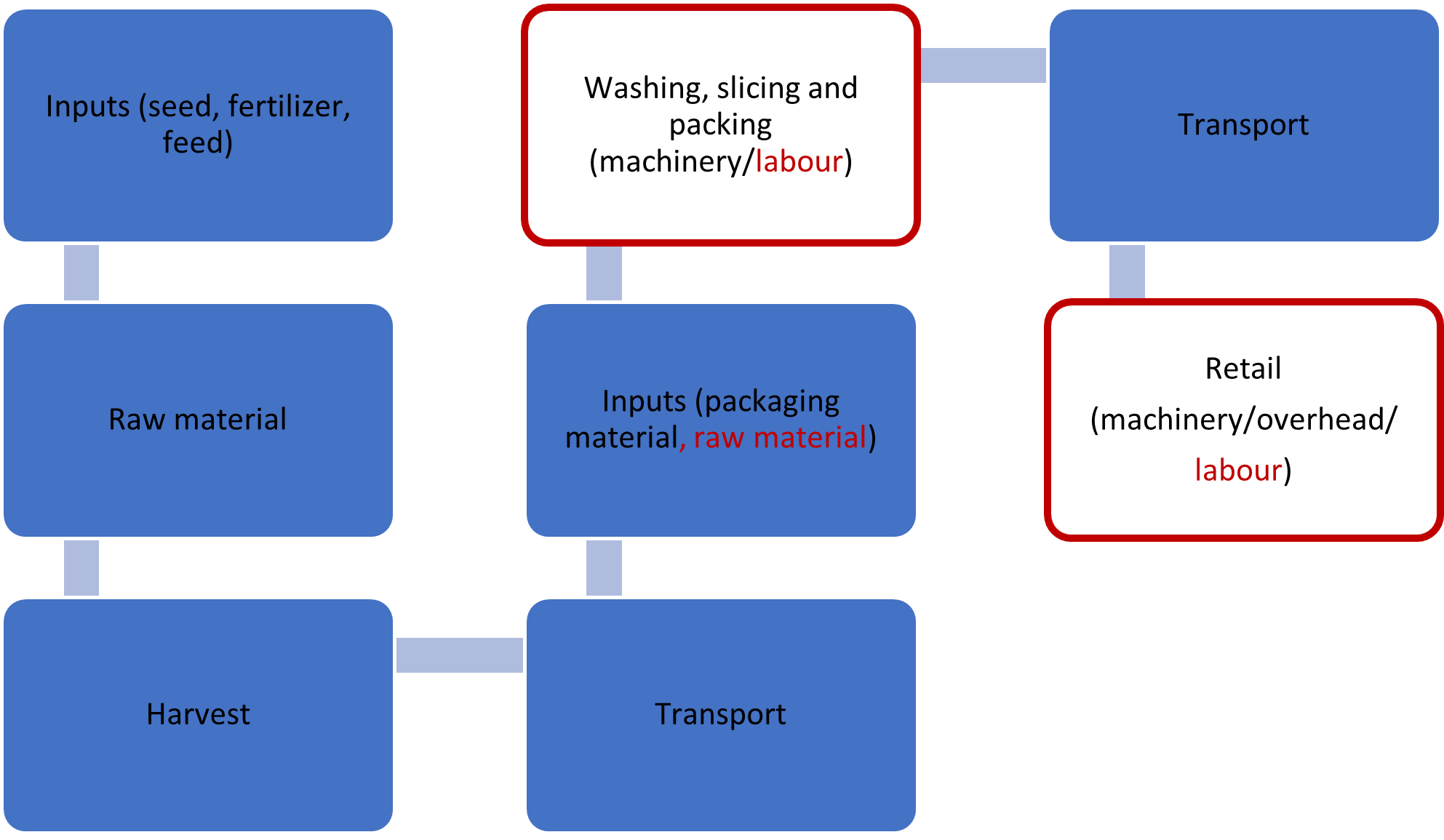

For example, a ‘Made in Canada’ product could come from a hypothetical supply chain with as few Canadian inputs as depicted in the figure below. The red outlined boxes are businesses located in Canada making the final transformation of the product and the red type represents Canadian direct costs (that don’t necessarily stay in Canada, either).

Simplified supply chain for hypothetical ‘Made in Canada’ product

The point of this example is to be critical of how little support for Canada a ‘Made in Canada’ product actually may produce.

A few more notes on complications before moving on to the big money question. If you’re letting that maple leaf guide your purchase decisions in the store, make sure a domestic content statement is nearby, like X% of this product is Canadian. A maple leaf with 11 points, like on the Canadian flag, is a protected trademark of the federal government. If the maple leaf doesn’t have 11 points, it is just a picture and doesn’t relate to a particular claim that can be verified.

Furthermore complicating matters is when companies start qualifying if a product was ‘Prepared in,’ ‘Refined in,’ ‘Processed in,’ ‘Packaged in,’ ‘Canned in,’ ‘Distilled in Canada’ etc. These claims are essentially referring to the portion of production where direct costs were incurred.

Claims get even more obtuse when a company like Sobeys will make their own claims about specific brands like Compliments. For example, on the FAQ section of their website, under Where are your products made? It says: if the product is ‘Prepared for Sobeys’ it is ‘Produced in Canada’ (same as ‘Made in Canada,’ according to the CFIA). If the product says ‘Imported for Sobeys’ or ‘Produced for Sobeys’ it is produced abroad.[iv]

From a marketing perspective, there is a lot of uncharted territory for how to communicate with customers about where their food ‘comes from.’ In many ways, it’s up to the individual company to choose their own level of transparency. While the CFIA is a large agency responsible for claims enforcement, their significant focus is on food safety, and their best tools are inspections, sample analysis, and complaints. With planned CFIA spending diminishing by tens of millions of dollars over the next several years, it may really pay to inform yourself on claims, whether they actually support your values, and whether they are worth paying extra for.

Who is benefitting from your dollars?

Canadian companies, Canadian retailers and Canadian producers

A third question to ask yourself is, who is benefitting from your dollars, and where? Buy Canadian doesn’t really define a ‘Canadian company.’ You can consider where the store is owned or operated, or who owns or operates the store. Canadian retailers are different from Canadian companies. They serve a Canadian retail market but they’re not necessarily from Canada. Walmart, for example, is an American Multinational headquartered in the US. But Walmart Canada is a Canadian retailer, headquartered in Mississauga, Ontario headed by Vanessa Yates, who originally from Australia, who is in charge of over 100,000 people in Canada. So is shopping at Walmart an act of buying Canadian?

If you think not you can boycott Walmart but only if you’re willing to also boycott its Canadian employees, and some truly transparent Canadian food companies like Equifruit. Equifruit is one of Canada’s fastest growing companies, headquartered in Montreal. It is B Corp Certified, Fair Trade International certified, woman-led, and by one of Canada’s Most Admired CEOs in 2024. Equifruit sources bananas from Ecuador, Peru and Mexico to sell in Canada but in Alberta they are only available in select Walmart’s (and Costco’s). Your decision to shop at Walmart (or not) has far more impact than you may think.

The big 5 grocery retailers, who control 80% of the grocery market in Canada,[v] are all headquartered in Canada and employ Canadian people. You have Walmart Canada and Costco Canada, the latter headquartered in Ottawa and employing 53,000 people in Canada. Costco though, is owned by institutional investors – primarily, the Vanguard Group, headquartered in Pennsylvania, Blackrock, headquartered in New York City, and the State Street Corporation, headquartered in Boston. Like Walmart, Costco sells products Made in Canada or produced by Canadian companies to varying degrees.[vi]

There is Loblaws, owned by George Weston Limited head-quartered in Toronto, employing 200,000 people in Canada. There is Empire, the Canadian owned giant running Sobeys, Safeway and IGA in the Canadian west, headquartered in Nova Scotia, and employing 128,000 people in Canada. There is Metro, but that’s all we’ll say on Metro because they don’t have stores in the west. From the numbers alone, that is roughly 500,000 private tax payers, paying some, oh say, $10,000 in taxes a year for arguments sake, all contributing to GDP and some $5 billion dollars in government revenue.

For information’s sake, between 2019 and 2022 the big 5 nearly tripled their profit on the margins while alternative grocer’s margins shrunk or disappeared.[vii] Those are your farmers markets. Local markets often have shorter supply chains, meaning they actually buy from Canadian producers. During the pandemic, researchers found that they not only passed on less of their higher input costs to consumers than large chains, but they were also able to adapt their distribution network more quickly,[viii] demonstrating a capacity to meet demand shifts.

Of interest in Alberta, independent grocers like Co-op and Freson Bros, Sunterra, and Community Natural Foods. all have some long-standing local history and support for local producers worth considering in your buy Canadian endeavours. Furthermore, find a local farmer’s market with the Alberta Farmer’s Market Association’s handy search tools.

What ‘Buy Canadian’ Could Be If We’re Smart About It

The buy Canadian choice is not just about what you buy, but who you buy from. In the long-run, it could be about using your dollars to demand domestic capacity to buy Canadian products from Canadian companies. That means getting literate about your food choices. Ultimately, it is our own domestic capacity to produce and manufacture food that determines what Canadian products are available. If you value supporting Canadian producers and companies, the Canadian economy, and Canadian people, making real sacrifices about where and how you shop and eat may be necessary. It doesn’t have to be hard though. In a global food context, buying Canadian is and always will be complicated and not a zero-sum game. Perhaps ‘Shop Your Values,’ is a more appropriate sentiment than ‘Buy Canadian.’ The two are not necessarily synonymous.

There are thousands of direct-to-consumer retail opportunities online and in-store that can help you improve your eating habits and shop your values. To help you with this, the next article from Ruby Rooster will synthesize some of these opportunities with easy-to-follow steps and resources.

‘Buy Canadian’ can be a lighthouse for sustainable, ethical solutions to systemic issues in Canadian supply chains. Let it not be a hostile, knee-jerk reaction to threatening rhetoric but an opportunity to improve your eating habits and your community, to complement trade, reduce emissions, increase supply chain transparency, support food innovation, security, resilience, quality, ethical sourcing, and the Canadian brand.

Remember, food is energy. Thanks for sharing food news with Ruby Rooster.

Not for commercial use. Copyright Ruby Rooster 2025. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ruby Rooster with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

This article is not legal, medical, health, or financial advice from a registered professional; it is for informational purposes only.

[i] Government of Canada (2023). Origin Claims on Food Labels. Retrieved May 8, 2025 from https://inspection.canada.ca/en/food-labels/labelling/industry/origin-claims#c5

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Retail Council of Canada (2025). Guidance on Made in Canada and Product of Canada Claims on Consumer Products. Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://www.retailcouncil.org/advocacy/food-grocery/guidance-on-made-in-canada-and-product-of-canada-claims-for-consumer-products/

[iv] Sobeys Inc (2025). Compliments FAQs. Retrieved May 8, 20205, from https://www.compliments.ca/en/faqs/

[v] Stephens P., Madziak V., Gerhardt, A., Cantafio, J. (2025.) Exploring price changes in local food systems compared to mainstream grocery retail in Canada during an era of ‘greedflation.’ Food Policy. Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919224001842.

[vi] Money Sense (February 3, 2025). Is Kirkland Canadian? Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://money.ca/news/is-kirkland-canadian#:~:text=What%20products%20sold%20in%20Costco,flavours%20such%20as%20strawberry %20banana.

[vii] Stephens P., Madziak V., Gerhardt, A., Cantafio, J. (2025.) Exploring price changes in local food systems compared to mainstream grocery retail in Canada during an era of ‘greedflation.’ Food Policy. Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919224001842

[viii] Ibid.